Even the sky isn’t the limit when it comes to human curiosity and our desire for exploration. Having already ventured into space and set foot on the Moon, the question for some time now has been where humanity will go next. And what comes after that. It is often said that science fiction inspires and leads scientific discovery and innovation. Star Trek, one of the first shows of its kind, has arguably played a seminal role in our space journey so far, inspiring renowned scientists like Stephen Hawking and Martin Cooper. NASA itself has documented how the series helped spark the imagination of its “planet hunters” searching for exoplanets. Books and films such as The Martian and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy have likewise stirred the minds of countless curious readers, many of whom later joined space‑tech efforts to turn speculative ideas into real missions.

No individual has perhaps played as pivotal and consequential a role in contemporary space ambition as SpaceX founder Elon Musk. Musk and his team have laid out concrete plans not just to reach Mars, but to eventually colonize it and make humanity a multi‑planetary civilization. SpaceX has designed a fully reusable transportation system called Starship, consisting of the Starship spacecraft and the Super Heavy booster, together referred to simply as Starship. According to SpaceX, Starship is capable of carrying up to 150 metric tonnes in a fully reusable configuration and up to 250 metric tonnes expendable. The journey to the Red Planet is expected to take around six months, and Musk has publicly targeted the late‑2020s Mars launch windows after uncrewed test missions planned around 2026. SpaceX notes that key technologies and industries such as power generation, resource mining, construction and transportation will be essential to building cities on Mars. The first human crews will be tasked with surveying local resources, preparing landing zones, deploying power systems and constructing early habitats.

Interplanetary travel missions are unlike any expedition in human history. When astronauts go to space, they endure some of the harshest conditions imaginable, and these missions test their limits both physically and mentally. The farthest humans have travelled from Earth so far is to the Moon. The Apollo 11 mission, the first to land astronauts on the lunar surface, took 4 days, 6 hours and 45 minutes from launch to landing. Mars, considered the most likely habitable planet in our solar system, is expected to take roughly six months to reach far longer than even the most brutal winters on Earth.

Spacecraft will be equipped with systems designed to support health and wellbeing, but certain constraints will remain insurmountable. For long stretches, astronauts will, in David Bowie’s words, be “floating in a tin can far above” home. The loneliness and alienation that will inevitably creep in are difficult to fully prepare for. Researchers and mission planners are now exploring every possible way to address these challenges, and AI has shown immense promise.

Recent films like Ridley Scott’s The Martian and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar have vividly imagined what future interplanetary and even intergalactic missions could look like. With spectacular imagery and effects, they convey the thrill, danger and gravity of such journeys. In Interstellar, two of the most memorable characters are TARS and CASE, pragmatic AI robots that are notably not humanoid. Their monolithic, modular design prioritizes practicality and resilience over human‑like appearance, yet they speak naturally, display humor and act as trusted crew members. They embody a vision of AI as navigator, technician, counsellor and friend, roles future spacefaring systems may be expected to fill.

AI robots are already at work in space. NASA developed one of the first humanoid space robots, known as Robonaut. Robonaut 2 (R2) was first deployed to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2011 and later returned to Earth. R2 is composed of multiple systems, including vision and image‑recognition modules, sensor integration, tendon‑based hands and control algorithms, many of which incorporate elements of AI. NASA explains that by working side by side with humans, or going where risks are too great for people, Robonauts will expand our capacity for construction and discovery in space.

CIMON, the world’s first AI‑powered astronaut assistant, spent about 14 months aboard the ISS during its initial mission. CIMON‑2, developed jointly by IBM, Airbus and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), was launched to the ISS on 5 December 2019 aboard the SpaceX CRS‑19 mission. Equipped with IBM’s Watson Tone Analyzer, CIMON‑2 uses linguistic analysis to detect emotions in astronauts’ voices and has been described as having a degree of emotional intelligence. It can navigate autonomously within the station using internal rotors, display facial expressions on its screen and provide conversational support while assisting with experiments and procedures. According to IBM and DLR, CIMON‑2 successfully demonstrated its capabilities in orbit.

With the advent of large language models and generative AI, such systems are poised to play an even more central role in future missions. Their ability to communicate fluidly in natural language has dramatically expanded their potential utility. AI‑powered medical assistants could help diagnose and treat astronauts, regularly conduct health assessments and develop personalized plans to manage emerging issues far from Earth. AI companions may support mental health by offering conversation, guided exercises and real‑time monitoring for signs of stress or isolation.

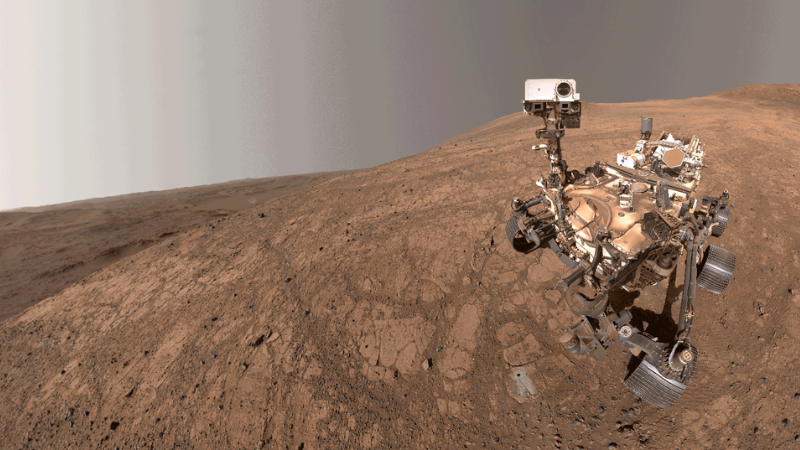

Autonomous rovers are already widely used on planetary surfaces to gather data and scout terrain. Equipped with more advanced AI, their autonomy and decision‑making will improve further, allowing them to take on more complex tasks, from scientific exploration to infrastructure inspection. Onboard AI systems could also perform continuous anomaly detection on spacecraft, flagging potential faults and carrying out routine maintenance tasks before they become critical.

In the coming decades, astronauts are likely to live and work alongside AI robots in many forms. Floating assistants like CIMON, dexterous humanoids like Robonaut, rugged planetary rovers and perhaps shipboard AIs reminiscent of TARS and CASE. These robotic and software crew‑mates will share a significant portion of the workload and, in long‑duration missions, may become counsellors and companions as much as tools. As humanity ventures further into the unknown, AI may prove as essential as rockets and life‑support systems in keeping explorers safe, effective and emotionally grounded