Modern life with all its comforts is the result of innovation and the endless refinement of technology. Every gadget, tool and appliance we use has been worked and reworked upon countless times. Experiment after experiment, trial after trial, iteration after iteration, everything we use today has been observed, examined, scrutinized and improved. Ask anyone who has built anything and they will tell you how they got to where they are.

They will also tell you that the final product they have now is very different from the idea they first conceived. They can walk you through the steps the process entailed, how each iteration made visible what needed to change, and how this cycle repeated until they arrived at what exists today. This process of changing inputs, watching how things play out, and observing how outputs vary is at the heart of research and development. That’s how techniques are fine‑tuned and technology improves.

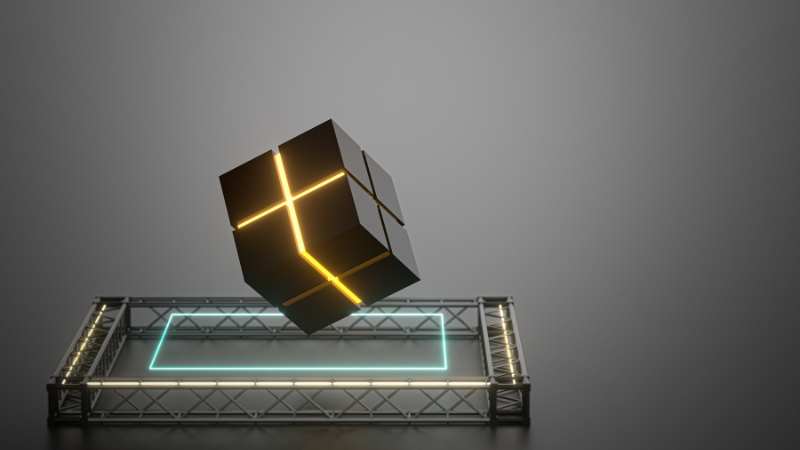

But what happens when you can’t examine how a particular process works? When the technique is shrouded in mystery? When the inner workings are in the dark and there is no clear way to understand why certain inputs result in certain outputs? And how is it possible not to know what happens inside something we built in the first place?

One area where this phenomenon appears with particular force is Artificial Intelligence. Specifically, it shows up in the deep learning algorithms that power many AI systems, and it is known as the black box problem.

What Is the AI Black Box Problem? Why Does It Exist?

At its core, the AI black box problem is about opacity. We cannot easily see or explain why complex AI models make the decisions they do. The outputs that AI systems arrive at are often unpredictable, and the path they take to get there is largely hidden.

To see why, it helps to understand how these models function. Many modern AI systems rely on deep learning, which uses artificial neural networks inspired by the human brain. These networks can involve billions of parameters and millions of artificial neurons, organised in many layers and interacting in highly non‑linear ways.

The sheer size and complexity of these architectures make it extremely difficult to trace how any given input flows through the system to produce a particular output. Even their own developers often struggle to give a clear, step‑by‑step explanation. This scale and non‑linearity are the main reasons the black box phenomenon exists.

Why the Black Box Is a Problem

Due to this lack of transparency, AI models can reach conclusions without offering any explanation, and the decisions they produce can be hard to justify in real‑world settings. A model may appear to perform well in testing, getting the right answers, but for the wrong underlying reasons, only to fail in new situations. When models hallucinate or generate nonsensical outputs, the opacity makes it hard to understand why.

This not only makes such systems less reliable, it also raises serious ethical concerns as AI is used in more consequential domains. In hiring, for instance, it may be impossible to know why one résumé was shortlisted while another was rejected, or whether the model has quietly absorbed biases related to race, gender or background from its training data.

Regulators are taking notice. The EU’s AI Act, for example, imposes explicit transparency and explainability obligations on “high‑risk” AI systems, requiring that they be designed in a way that enables deployers to interpret outputs and use them appropriately. Foundation models and agents add further complexity. They operate over billions of features, can maintain internal memory, and make decisions based on internal states that are not directly observable.

Large language models (LLMs) introduce yet another layer. They may follow different internal paths, even when prompts are only slightly modified, and the route they take through their parameter space is not explained to users. Not knowing how a model reasons makes it harder to detect failures and harder still to fix them when they do not behave as intended.

Emerging Solutions and How to Tackle the Black Box

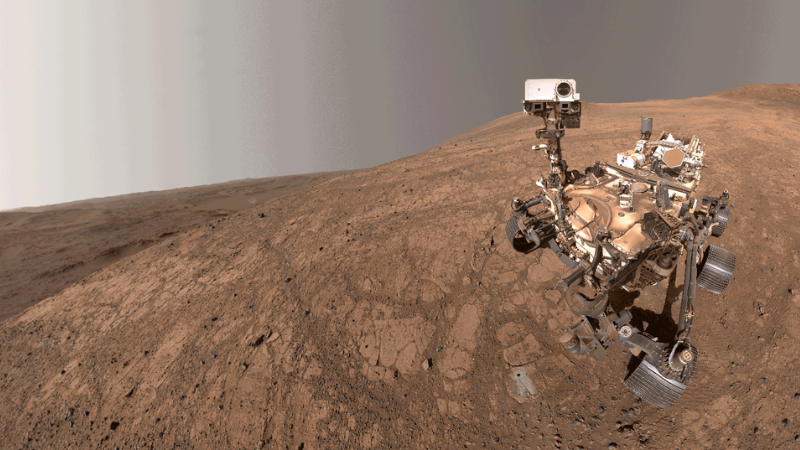

Addressing the black box problem is about more than simply adding explainability on top. At its core, it requires mechanisms to verify accuracy and behaviour at multiple stages of the AI lifecycle. That improves reliability, but it is also crucial for maintaining human control as models grow more powerful.

Google, for instance, has been working on what it calls “Explainable AI,” including tools that provide feature attributions and counterfactual explanations for model predictions. In a counterfactual, the system effectively asks, “What would the output have been if certain input information were different or missing?” This helps build a picture of which features the model is relying on when making decisions and what it is ignoring.

Anthropic has published research titled “Mapping the Mind of a Large Language Model,” in which it claims significant progress in understanding the inner workings of its Claude models. Using a technique known as dictionary learning, the team identified patterns of neuron activations called “features”, that consistently light up when the model processes certain concepts. These features can correspond to topics, styles or behaviours.

Crucially, Anthropic found that manipulating some of these features can change the model’s behaviour, suggesting that they are not just correlated with concepts, but causally involved in how the model represents and reasons about the world. The researchers also note that some features may help address concerns around bias and autonomy by making it easier to see and adjust what the model has learned.

Beyond research tools, control and explainability depend on good practice throughout the pipeline. Stronger data governance, using well‑defined, versioned and transparent datasets, should be the foundation. Clear frameworks for evaluating how a model behaves, including simulations of failure scenarios, are essential. High‑impact models should be monitored even at runtime, and their pipelines stress‑tested to ensure they behave safely under unusual or adversarial conditions.

The black box problem is one of the most important blind spots in modern AI. But it is not an unsolvable mystery. With sustained effort, from better data practices and regulatory standards to technical advances like counterfactual explanations and feature‑level interpretability, AI systems can become more transparent, robust and reliable.

If we treat explainability as a core requirement rather than an afterthought, tackling the black box will not just make AI safer. It will also build the trust needed for AI adoption across industries and help ensure these systems remain tools we understand and control, rather than opaque engines whose inner workings we can only guess at.