Chess has long been the ultimate game of strategy. Many great minds have been humbled and fascinated by the hidden world inside its 64 squares. It has been estimated that the game tree explodes so quickly that even after only a small number of moves, the number of reachable positions already runs into the tens of billions, which helps explain why exhaustive calculation is impossible for humans. Chess has been the arena where many philosophers, scientists, mathematicians and people who seek to challenge their grey matter have competed against each other to prove intellectual superiority. Indeed, excellence at this game has been widely acknowledged as a mark of intellectual prowess. The structure of this game tests a player’s ability to evaluate move sequences multiple layers deep. Spotting familiar structures and recognizing patterns to exploit strategically are crucial to playing this game well. Yet no one can calculate every line of possible game play and moves have to be made under uncertainty. Doing all this under the pressure of time is a serious test of problem‑solving ability.

Why Chess Was Ideal for Early AI

Now computers are machines built for the primary purpose of solving problems. So it wasn’t long after computers came into being that scientists were curious if computers could play this game that had become a proxy for reasoning and thinking abilities. From a programmer’s perspective too, chess almost seemed to be tailor‑made. It was a game that could be encoded exactly with clear rules, no hidden states (unlike poker) and with a massive archive of recorded games available. The game also has a built-in scoring system, which made it the ideal controlled environment where algorithms could be tried and tested.

Claude Shannon, a mathematician and researcher at MIT, in his groundbreaking paper titled “Programming a Computer for Playing Chess” published in 1949, also highlights that the “chess machine” is ideal to start with because the problem is neither so simple as to be trivial nor too difficult for a satisfactory solution. He states that a solution of this problem will force us to either admit the possibility of mechanized thinking or to further restrict our concept of “thinking” altogether.

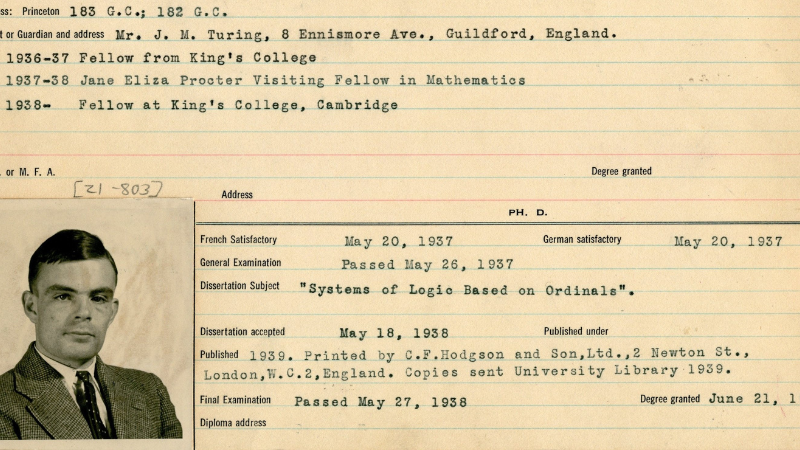

Turing, Los Alamos and the Birth of Computer Chess

Across the Atlantic, British scientist Alan Turing wrote the first full chess program specification, which he named “Turochamp”, around 1950. The algorithm could in principle move pieces after calculating the next possible moves of the opponent and play an entire game of chess. This program was too complex to be executed on any computer at the time and Turing couldn’t see his program in action on a computer before his death in 1954. Although the playing strength of Turochamp was later found to be weak, it played an important role in the development of future chess engines and showed that serious chess play by machines was conceptually feasible.

Many more attempted to build their own chess‑playing programs in the years that followed, most notably the one developed at Los Alamos Laboratory which used a reduced 6×6 chessboard to make the problem tractable on early hardware. The term “Artificial Intelligence” was also introduced for the first time in 1956 at the Dartmouth conference, an event widely regarded as the birth of AI as a formal research field. In the year after that (1957), Herbert Simon famously predicted that a digital computer would be the world chess champion in ten years. The Nobel Prize‑winning economist and thinker helped popularise the idea of chess being the “drosophila” (fruit fly and ideal experimental subject) of artificial intelligence, an analogy first attributed to Soviet Russian mathematician Alexander Kronrod and later examined in depth by historians of computing.

From Experiments to World‑Class Engines

In the 1970s and 1980s chess engines continued to make rapid improvements and computer chess championships were now held periodically. Programs could now beat amateurs and, in some conditions, even very strong players. Custom chip designs were tried and used in an attempt to increase playing strength, and micro‑computers were also programmed to play chess. In 1989, Deep Thought defeated grandmaster Robert Byrne in a tournament game, a landmark moment that showed computers were closing in on elite human performance. A detailed list of major events and breakthroughs in the history of computers and chess is documented in this Chess.com history.

But what happened in 1997 was something no machine had ever done before. This event ushered in a new era in the field of computer science and artificial intelligence. IBM’s Deep Blue beat reigning world chess champion Garry Kasparov 3.5–2.5, becoming the first computer system to do so under standard tournament time controls. Kasparov, who had beaten an earlier version of Deep Blue 4–2 the previous year (1996), now grudgingly paid his tribute and admitted to the computer being far stronger than many expected. IBM had used a method called alpha‑beta pruning and other search optimizations, implemented on custom VLSI hardware, allowing Deep Blue to evaluate around 200 million positions per second, an approach often described as “brute‑force search” guided by heuristics. The AI community, as pleased as they were, were also dissatisfied with the fact that the computer managed to win primarily by searching enormous numbers of positions, rather than because it was capable of creativity and thinking like a human.

AI‑powered chess engines have evolved greatly since. Stockfish, introduced in 2008, although still a search‑driven engine, was based on sophisticated heuristics. Stockfish combines brute‑force search (minimax, alpha‑beta pruning and related techniques) to explore moves and human‑crafted heuristics (piece values, king safety and many other positional features) for position evaluation and understanding.

Neural Networks, AlphaZero and the AI “Super‑League”

Chess engines based on neural networks were being developed in the next decade. These engines learned how to play chess by training against themselves or on large game databases and have a style of playing that many observers describe as closer to human intuition. They still rely on search, but can lean more on learned evaluation functions than on purely hand‑tuned rules. AlphaZero, developed by DeepMind, defeated Stockfish in 2017 using a deep neural network trained entirely by self‑play combined with Monte Carlo tree search. In its matches against Stockfish, AlphaZero prioritised long‑term positional advantages over immediate gains and showed a willingness to sacrifice pieces for strategic advantages, enabling it to play in a more dynamic and adaptable style that impressed many grandmasters.

AI‑powered chess engines have become so good at the game that it is now virtually impossible for any human player, including the world champion, to beat the very strongest engines under fair match conditions. They are in a weight class of their own and it is only fair to have them wrestle with each other, which they do. In 2025, for example, OpenAI’s o3 system beat xAI’s Grok‑4 in the final of Kaggle’s AI chess tournament, an event that pitted leading AI models against each other in controlled chess matches.

Is Chess Really the “Drosophila” of AI?

Researchers in this paper have examined and written about the role chess played in the development of AI and have concluded that if the primary measure of an experimental organism is to produce fundamental theory, then chess is probably not the drosophila of AI in the strict sense. But that being said, for historians of science and technology the analogy between chess and drosophila and the role that chess has played assumes great significance. They believe that the lessons to be drawn are methodological and are widely applicable.

Regardless of how significant or insignificant an impact chess has had on AI theory, AI has revolutionised chess. Strong engines, online databases and training tools have transformed how players prepare and analyse games, and top professionals routinely use engines as sparring partners and analytical assistants. Ironically, after teaching computers and AI to play chess for so long, humans are now improving their game by playing against and alongside AI.